I bought a pulse oximeter, one of those little fingertip sensors you see in hospitals, partly out of curiosity, partly out of boredom. The idea was simple: if programming is a marathon of attention, maybe I could see what my body was doing when my brain started to lag.

It turns out, a $20 device can tell you a lot.

After a week of logging readings during coding sessions, a pattern appeared. When I was deep in flow, my oxygen saturation (SpO₂) stayed steady, and my heart rate had a subtle rhythm. It was up slightly when debugging, down when refactoring. But when I slouched, skipped water, or pulled a too-long stretch without standing, my SpO₂ dipped a few points. Nothing dramatic, but enough that I felt the difference: foggy thinking, slower reactions, more tab-switching.

It was oddly validating to see the physiology of burnout in real time.

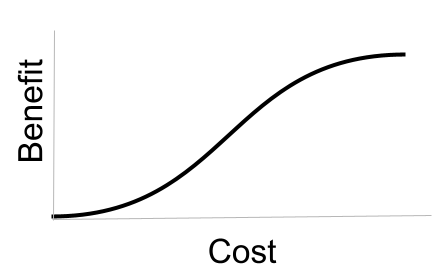

Then I started noticing something else: interpreting those readings felt like doing data science on myself. One measurement means nothing. But the trend over hours told a story. Which made me think about healthcare more broadly.

I even had a little spike at one point – scary! But I had to take it in context. As they say, think horses, not zebras.

Doctors deal with this same puzzle at scale. A single pulse-ox reading can be misleading; what matters is the pattern and the context. I started appreciating how fragile and dynamic the human baseline really is, and how much judgment goes into deciding what counts as “normal.”

Programming teaches us to respect abstraction and precision. Healthcare, I realized, teaches the opposite: humility in the face of variance. My little experiment bridged the two.

So I’m still using the pulse oximeter. Not to “optimize performance,” exactly, but as a reminder: your brain runs on oxygen. Your best code might start with a deep breath and a good posture check.